The Tea

When in China, drink like the Chinese drink.

That’s the goal, and the beverage of choice over here is, as you probably know, tea.

Tea is one aspect of Chinese culture that cannot be exaggerated by even the most embarrassingly inaccurate caricatures. It truly is everywhere: tea is served at nearly every restaurant and cafeteria you enter, you receive boiling water and teabags every morning in your dorm room, and you’ll more often see thermoses than water bottles in people’s hands on the street. Honestly, the unofficial adoption of tea as the national drink of China is (in my humble opinion) an excellent decision. After all, while tap water is risky and alcohol doesn’t quench one’s thirst, boiling water is bacteria-free, offers no health risks (other than burning oneself, of course) and, on the contrary, is allegedly healthier to drink than cold beverages! Furthermore, tea comes in so many forms and varieties (from the medicinal stuff to the nasty wannabe Starbucks knockoffs) that, like wine, one will never run out of new varieties and subtleties to discover. The wine analogy is accurate on a cultural level, too, insofar as China’s attitude toward tea mirrors the wine aficionados of the West.

During my time here in China, I had the wonderful opportunity to visit both a tea museum and tea plantation. And of all the experiences I’ve had, I do believe that nowhere was the culture shock more pronounced than in experiencing China’s devotion to tea. There aren’t as many pictures in this post as usual (for reasons you will shortly understand), but hopefully the narratives I’m coming home with will do at least some justice to the experience! I’ll try a slightly different post format this time, where the story will go along independently of the images, which will have separate captions describing them.

In any case, without further ado…

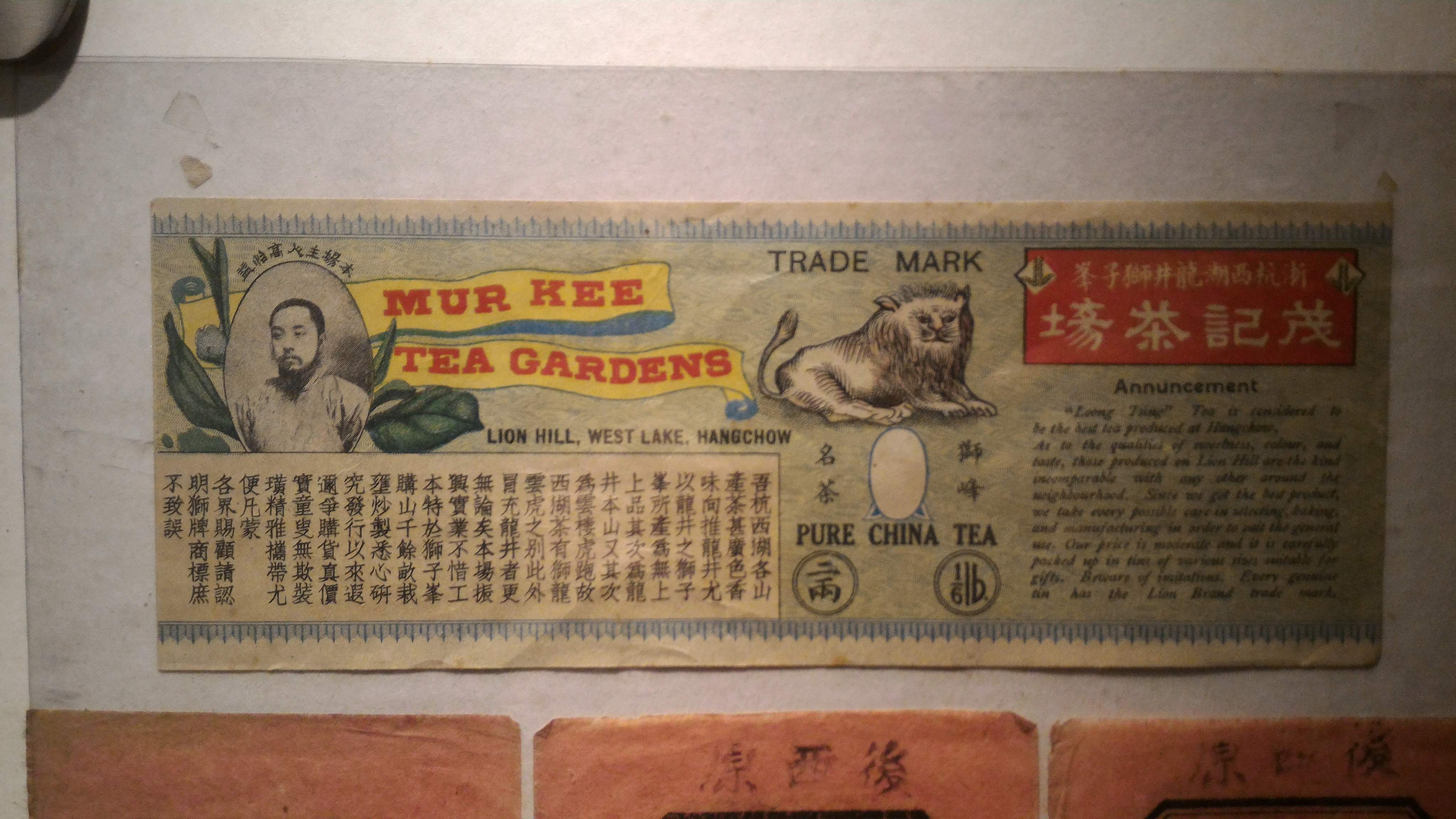

The most famous tea in China is without a doubt Longjing (龙井: “dragon well”) green tea. The only place in the world that it is grown is in the rural villages around West Lake in the city of Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. Tea labeled “Longjing” from any other location (Sichuan, Yunan, etc.) is considered fake. Hangzhou takes their status as the sole producer of authentic Longjing tea very seriously; to visit one of these fabled tea plantations to get firsthand experience of the substance is only natural for any tourist in the area.

As the bus drove into the countryside, several relatively large houses slid past our view.

“Tea farmers,” explained our tour guide, “is one of most rich people in China. Actually only some business men more money than Longjing farmers.”

How much do they sell this stuff for? I wondered. In restaurants, tea seems to be too cheap to charge for!

Oh, how ignorant I was.

Arriving at the location where we were to be given a tour of the farming and processing procedures, we stepped off the bus into a humid gray day and meandered over to the nearest Longjing tea bush. They weren’t by any means in short supply; these bushes were about chest high on average and lined every hill and valley we drove through. Seeing the luscious, deep green leaves on the bush we were examining, I wondered why this one hadn’t yet been stripped clean.

“Actually this one already harvested by farmers,” our guide corrected us. “Good quality Longjing tea, only sprout leaves used, maybe one or two on a twig.”

We were shown a recently harvested leaf and realized that they were hardly more than sprouts. Leaves any longer than your pinky toe were already too mature, and would be left on the bush until the next season. The ideal Longjing tea leaves, the guide informed us, should look like a small bird’s tongue protruding from its mouth. Me being the pragmatic guy I am, I naturally assumed that this was just a bunch of snobbish talk. However, further research revealed that such picky harvests are in fact vital to creating a tea with the proper chemical balance: extended exposure to the elements produces oxidation which ruins many of the precious nutrients within the leaves.

Naturally, to pick just the sprouting leaves on an individual or two-by-two basis, no machines are suitable for the task: only hand-picking will do the trick. There are three harvest times–one in Spring, Summer, and Autumn–and each harvest is supposedly of a “lower quality” than the previous one.

Okay, I thought, that imposes a bit of a limit on how much of this stuff is actually produced. How many kilograms of tea are harvested per bush?

That answer depends on when during processing you are measuring the weight. Harvested leaves must be dry-fired in a large iron pan almost immediately upon separation from their host bush, so as to avoid the dreaded effects of oxidation. The first firing evaporates external moisture, and the second firing yields leaves in their final, dry (but not yet shriveled), sterile state. To avoid defacing the bird-tongue-like beauty of these little Longjing sprouts, the firing process must also be done by hand. I do not exaggerate when I say that these tea farmers stick bare palms into pans of roasting iron and spread the tea leaves around the bottom without so much as a blister appearing on their own fingers. Either those farmers’ hands are made of rubber, or those Longjing tea leaves should be used as insulation in fire-safe buildings. Holy cow.

So, the amount of tea per bush? Let’s just say it’s not measured in kilos, but in grams. And we were standing in the only plantation officially recognized by China as producing this product.

Oh, and by the way, 1.3 billion people want to buy this stuff. So it’s pretty valuable.

After strolling around the plantation for a little while, we were escorted into a small building with simple, traditional Chinese architecture, and then through some sliding doors into what looks like a conference room. A long oval table stretches the length of the room, and on one end are situated several dozen bound paper packages and green cans. The group is seated and everyone is given an empty glass.

A smartly-dressed young woman enters the room and closes the doors behind her. Taking her place at the head of the conference table with the packages and cans, she proceeds to explain to the group where and how Longjing tea is enjoyed. At the same time, her hands, moving seemingly independent of her mind, begin unwrapping one of the packages and depositing a pinch of the contents into each of our glasses. Boiling water is added, and the Longjing tea in front of each of us begins to steep.

Typically, the highest quality Longjing tea (the first pickings) are reserved specifically for government officials and for gifts distributed by Chinese foreign ambassadors. The little that remains is often auctioned off, yielding prices up to thousands of US dollars for a single gram (hardly enough to make a single glass). Because of its value, a person typically re-uses the same tea leaves in a given glass or thermos for an entire working day, refilling it with boiling water whenever necessary.

“Okay, time to begin appreciating Longjing tea,” announces our lecturer. We raise the glasses to our lips, but she scolds us and tells us first to swirl the tea in our glasses and then inhale the steam. …So this stuff really is supposed to be consumed like wine.

Okay, we’ve sniffed it and it smells like collard greens. Now we flex our lips in preparation to consume the liquid and–

“Stop, you first need to look at Longjing tea. Hold glass like this and open wide eyes.”

She cups her hand over the glass and directs the steam from the cup into her left eye. Reluctantly, we all follow suit, and switch eyes on her command.

“This cures cataract,” explained our guide. “After look at computer for all day, you should look at Longjing tea instead.”

Okay, now it’s definitely time to start drinking it. After blowing the leaves out of the way, we take some tiny sips of the scalding hot liquid and, well, it tastes pretty good! “Collard greens” is still the first thought that comes to my mind, but that isn’t to say that the gustatory experience was unsatisfactory–on the contrary, I greatly enjoy collard greens, and I was perfectly fine drinking collard green broth if that’s what they do here in China.

Little did I know how much more this liquid was than simply “collard green broth.”

While we were sipping away, our lecturer was busy filling up a glass with her own mixture of substances, while talking away at a pace that would make Mr. Shamwow proud. Beginning with a healthy spoonful of rice, she explained that she was mixing together a scaled-down chemical equivalent of a person’s typical daily diet. She proceeded to add various oils and syrups, ranging from soy sauce to peanut oil to lard to molasses, and mixed the glass’s contents together into a brown mush.

“Some are people who drink water cleanse out diet,” she informed us as she poured a glass of water into the mush and swirled it around. “But not very effective.” The water was poured out again, much more turbid after the treatment, but leaving just as much mush in the original glass.

“Now we try same thing, but with Longjing tea.” She poured more water into the glass, then produced a small pill from one of the boxes on the table. “This same as ten cup of Longjing tea. You can also buy here and take, like vitamin.”

Into the glass the pill was thrown, and the mixture was carefully swirled once more.

“Now we empty again.” The disposal container received the second batch of dirty water–this time pitch black as it was poured away. A collective gasp went up from those who looked into the original glass of mush.

All that remained were fresh, white grains of rice.

“So you see, very good for body!”

Now, I don’t actually know how healthy it is to be drinking a liquid that is capable of extracting any visible presence of salt, sugar, and fat from one’s intestines. On the other hand, we just witnessed what seemed like pure witchcraft, and not one of us could claim to be left unaffected by the dramatic performance.

Our presenter, seeing our wide eyes and gaping mouths, knew it was time to make her strike.

An assistant was called in and the two women began throwing open the brown paper packages, revealing every shade of green Longjing leaves imaginable. The now mystical scent of collard greens filled the locked, windowless conference room. The orchestrator of the presentation slipped on a pair of skin-tight white gloves and picked up one of the green canisters.

“The leaves still fresh from roasting, not packaged for you yet,” we were informed, as the lid of the canister was popped off by those anonymous gloved hands and the empty, stainless inside was presented to the audience. “We package here for you now.”

A white glove dove into the mounds of Longjing leaves and pulled out a few handfuls, depositing them one by one into the canister until tea was piled to the top.

“This look full, but be assured,” warned our saleswoman, with rising urgency, “some settlement may occur.”

Placing a gloved hand over the top of the can, she bashed the bottom of the can into the table several times. While the sound was still ringing in our ears the hand was removed, revealing a can only two-thirds full.

“Is why we pack here, so you see we pack actually very full.”

Again and again she scooped up tea leaves, packing them into the can with force that must have rivaled the vacuum bags some of us used to bring our clothes to China. The lid was finally crammed onto the top, and the can was passed to the assistant who mechanically sealed it closed and rested it upon her hand.

“So you see, very full. If you doubt, please pack yourself.”

Other products were set out on display before us, from Longjing tea cakes to the ultra-concentrated colon-cleansing pills that sterilized the rice. After everything had been presented and positioned with care, the statement that everyone had been waiting for was uttered.

“You not barter here, we set fix price. For high-quality Longjing tea, one canister, regular price 600 yuan. We give to you half price, 300 yuan. You may pay RMB, USD, or the credit card.”

We all began to cast sidelong glances at each other as we shuffled through our wallets. This stuff obviously wasn’t the “first picking” seen at auctions–the price was too unbelievably low for that–but nonetheless, we had just seen with our eyes and tasted with our tongues the substance that was now being packaged before us, so we had little excuse to object to the trade.

Large stacks of bills started trading hands. As I watched my peers, my only thought was how illicit this whole process seemed to be: sitting around a conference table in a locked room with no decor, hungrily observing gloved hands pack mysterious dried leaves into sealed canisters to be passed along to a customer for a large sum. When we were finally released into the open air again, hardly anybody carried their purchases in their bare hands: the vast majority left these goods tucked away with care in the bottom of a purse or backpack. Some people could be observed absentmindedly tapping their bags occasionally to reassure themselves that their purchase had not left them.

I only hope that we are not caught in customs returning home.

And that’s the story of my experience with the culture of tea in China. Needless to say, the process left quite a significant impression on me, and I definitely believe that, regardless of its mystical and prodigious alleged properties, it will take a much more extensive role in my diet back home in the United States!

So far, I’ve located green tea popsicles, green tea toothpaste, and green tea ice cream here in China. There’s no doubt that I’ll be paying premium to get my hands on the stuff back home. Say goodbye to my poor wallet…