Access vs. Ownership

Recently I came across advertising online for a new co-living experiment taking place in Los Angeles. The name of the startup is PodShare. Essentially, the goal is to provide customers with location-independent access to a minimal set of resources necessary to live and work effectively in an urban environment. A bunk on a wooden frame, a charging station, and a chalkboard identifying the inhabitant are included in the package; doors, locks, and curtains are not. Aside from the bed itself, all areas within a PodShare location are public: the refrigerator and cooking utilities are shared, workspaces are common, and the restrooms are handled dormitory-style. Maintaining a clean and safe environment is as much the residents’ job as it is the staff’s, in the sense that everyone’s space can be seen from all angles, creating an aura of community watch.

If this description is hard to visualize, a good video providing an overview and history of the startup can be found here.

My initial reaction to this foreign living concept could be described best as a shameful terror. Terror, because I couldn’t imagine living in a situation so hostile to privacy and ownership of space. Shame, because in the culture that is starting this movement towards “Housing as a Service,” I recognize values and visions that I myself hold dear. Would rejecting this development make me a hypocrite?

In truth, the initiative of PodShare makes several steps toward a lifestyle that I have learned to esteem. To enjoy a content and fulfilling life in such an environment, you can’t have too much baggage: there aren’t many nooks large enough for one to unload their extra belongings, and there aren’t many ears patient enough for one to unload their ponderous past. “Podestrians,” as they are called, must minimize their possessions to the bare necessities. Wherever one life is lacking, another life is prepared and encouraged to fill the gap.

The environmental benefits are also considerable. The most bare-bones apartment complex that could accommodate the same number of men and women would require at least three times the land area and an order of magnitude more capital resources, not to mention the marginal costs and inefficiencies associated with independent thermostats, water lines, and electric service. Furthermore, splitting the community into individual houses would practically necessitate the construction of a new subdivision: an impossibility in any principally urban environment.

Taking the idea to an even larger scale, PodShare claims that if it were to expand its influence far enough, one would no longer need to book a hotel when travelling. After all, a bed in one location is a bed in any location with a vacancy–just check out of your hometown PodShare and catch a bus to your new location! How inconceivable that freedom is to the modern American citizen: the concept that moving across the country for a week, month, or indefinitely could be as simple as packing some carry-ons and catching a flight. Realtors, mortgages, and moving vans need not apply. Sell your house, and ditch that timeshare too: your bed is your timeshare now.

PodShare challenges our very definitions of house and home. “The future is access, not ownership,” claims Elvina Beck, the founder of the company. Millennials invest in gym memberships, public transportation, and music streaming services rather than purchasing the physical capital necessary to enjoy these luxuries for ourselves. Why not extend that idea to our very homes?

I do agree that, in the general case, owning less can lead to living more. Our culture in the United States has lost much of that compassionate, cooperative nature that first brought society together when individuals would have failed living alone. To put less reliance on the grasp of one’s own two hands, and instead seek to be a strength in others’ weaknesses as they likewise provide what you may lack, fills one’s soul in a beautiful and irreplaceable manner.

But to what extent must we deny our own desire for control over physical possessions to reap the intangible benefits of a cooperative lifestyle? Are there not memories, emotions, and even fragments of our identity engrained in our living spaces that could not exist without a sense of locality, of ownership?

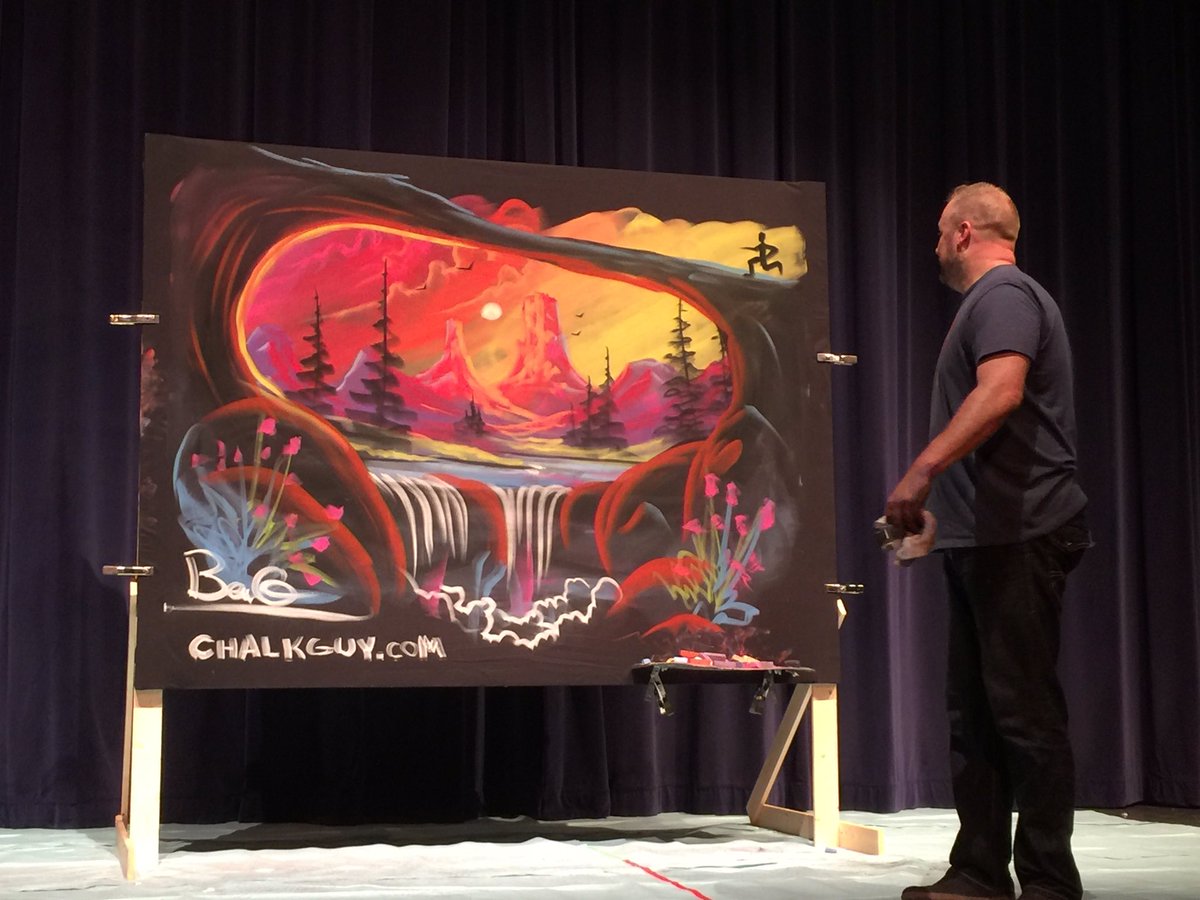

Motivational speaker Ben Glenn offers a powerful example of this concept. To this day, I can recall with vivid detail the Spring evening in 2009 when I witnessed him transform a black canvas into an breathtaking explosion of variegated color before our eyes. The audience journeyed with him step by step through the discovery process of artistic creation, and by the end of the experience we all felt as though we, too, owned the final work. Watching Ben share the exact same message at a different venue or via a different medium holds none of the same gravity for me, because my ownership and identity is contained in that one particular event, time, and place.

Would I be satisfied if, rather than attending that 2009 conference, I simply received a recording of the event, to be viewed on demand at any location or time? More importantly, if I had never experienced the original, would I even know what I was missing from the experience?

I do not believe I could describe with any accuracy the psychological difference between owning a home and having geographically-independent access to shelter, but I can only imagine that the effect would be similar to replacing such an intimate artistic experience with a recording. Though the instrumental value of housing has been demonstrated to be extractable into an on-demand construct, the spirit of home feels tied intrinsically to geography. Stripping ourselves of that luxury may not leave us physically homeless, but surely impoverished in spirit. As Yi-Fu Tuan would perhaps characterize the change, we would be accumulating the freedom of space at the expense of the identity and security of place.For a fascinating and edifying discussion on this topic, see Tuan’s work Space and Place.

For much of His ministry on earth, Jesus was truly homeless. "Foxes have dens and birds of the sky have nests, but the Son of Man has no place to lay His head," Jesus stated in response to a scribe's possibly naive proclamation of devotion.Matthew 8:20, HCSB Were His disciples willing to give up not only the physical comforts of shelter, but the very identity tied to their earthly homes, in order to accept adoption into God’s kingdom by Christ’s sacrifice? In what capacity is my worldly identity preventing me from perceiving the transformation that God so desires to work in His child and slave?

And on a deeper inspection of Christ's life, giving up house did not mean giving up home. His ties to his earthly family were not lost: rather, He found His family multiplied to all who followed the will of His Father.Matthew 12:49-50 He shared meals with brothers in the houses of the rich and poor, in the city and on the beach, with intimacy and with thousands. He invested none of His identity in an earthly dwelling, and yet He has arguably produced the greatest impact on history and society that any individual has ever effected.

I’m not ashamed to admit that, given my upbringing and human nature, the idea of housing as evanescent “access” in contrast to home ownership scares me. But looking at the life of my King, as well as the consequences of our past and our hopes for the future, I believe that this physical and cultural transformation may have the potential for great salutary good, should we give it the proper thought and introspection.

…And let’s be honest, PodShare has no plans for global domination by any extent: they still receive most of their business from millennial vagabonds and summer camps. We have ample time to reflect and discuss!

What are your thoughts on this housing movement? Let me know in the comments below.