Batched Processing in RxJS

When you have a ton of data that all needs to be processed, reactive programming makes the implementation easy to read, terse to write, and efficient to run. But when the data isn’t all needed, and processing the full stream is prohibitively expensive, more esoteric methods are necessary.

Say you have an array or stream of image files. You want to send them off to a service that runs image recognition, to identify pictures with cats in them. You want specifically the first four pictures with cats. Not just any four pictures with cats: perhaps the source array is already sorted by timestamp and you want the most recent four cat pictures.

Stream processing, asynchronous actions… This sounds like a job for reactive programming! However, you have a couple of unique concerns:

- The image recognition API is expensive to call. You don’t want to be charged for unnecessary requests.

- The image recognition API takes a long time for each file. You want to parallelize your processing, if possible.

Even with those considerations, you’re pretty sure some creative pipelines will do the trick. You bust out your RxJS library and get started.

Calling an asynchronous API for each item in an observable stream is a classic use case for one of the *Map operators. Every operator in that family will create a new stream for each item in the source stream, then collapse the outputs into a single stream to pass down the pipeline.

Some of the map operators are clearly inappropriate:

switchMapdrops old streams as soon as new source data comes in. We don’t want to lose any responses from the API.exhaustMapignores the source data stream while it waits for each created stream to complete. We want to check every image until we have four cats.

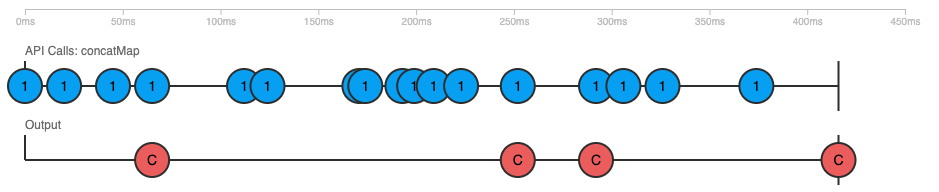

We really just want concatenation of our API calls, so concatMap seems like a good choice. Our pipeline would look something like:

sourceImages$.pipe(

concatMap(identifyImage),

filter(isCatImage),

take(4)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);It’s a clean pipeline! But in practice, this implementation processes the source images serially. Each API call must be returned before the next image is sent off. For a slow API, such serial processing is undesirable.

We’ve got a fourth member of the *Map family: mergeMap. On the surface, it looks like precisely the operator we need.

It creates child streams and merges them into the output stream as soon as input data arrives.

Implementing it yields nearly identical pipeline code:

sourceImages$.pipe(

mergeMap(identifyImage),

filter(isCatImage),

take(4)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);Testing it out yields a result worse than we started with: the order of the source images is no longer preserved. We start seeing cat pictures from decades ago, simply because they happened to be the first ones returned by the API.

As it turns out, the serialization of streams in concatMap (only creating a new stream when the previous one has completed) is a feature unique to that operator.

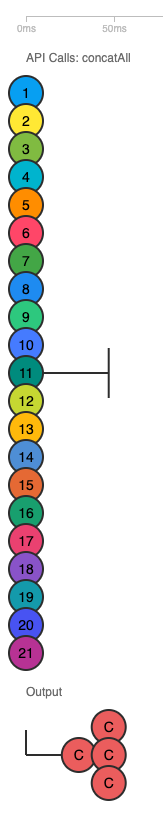

If we simply split out the “map” part of the operator from the concatenation, we get the best of both worlds:

- All of the streams are created up front (in the

mapoperator) - The order of the streams’ output is preserved

In between map and concatAll, each object in the stream is… itself a stream. Streamception!

sourceImages$.pipe(

map(identifyImage),

concatAll(),

filter(isCatImage),

take(4)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);This pipeline fixes both our ordering issue, and also runs completely parallelized. We get super excited, until we view our monthly bill from the image recognition service. As it turns out, this pipeline sends every single image to the API, as soon as it shows up in our source stream. We might send off thousands of requests before the four cat images are identified, even if the cat images are the first four images in the source stream!

If you’re trying out this code on your own, you might find that your map/concatAll implementation did not parallelize like you wanted it to. Most likely, it’s a result of implementing identifyImage as a pure RxJS stream, otherwise known as a “cold” observable. The difference between cold and hot observables is simple to state, hard to internalize:

- Cold observables have their data created inside the observable

- Hot observables have their data created outside the observable

Cold

If I make an Observable from an array, from([1, 2, 3]), all of the data is already there. The computer doesn’t have to wait for anyone to get data back to it for the stream to both start and complete immediately.

- They don’t start emitting values until someone

subscribes to them - They run a separate, unique pipeline for each subscription (they are “unicast”)

Hot

Hot observables are made from things like Promises. The computer is waiting for someone else to get back to it, and the computer will emit whatever it receives as soon as it arrives.

- They emit items upon arrival, regardless of subscriber count

- They send data through a single pipeline, no matter how many subscribers (they are “multicast”)

Returning to our pipeline above: if we map data to a hot observable, the API request goes out immedately (no need for a subscriber). The concatAll does end up subscribing, but the API request is already processing at that point. As each API call returns, concatAll will subscribe to the next one in the stream. Most likely, that latter API call will have already returned, so concatAll receives an immediate value, and continues.

On the other hand, mapping to a cold observable doesn’t kick off any process at all. The concatAll subscribes to the first observable, and waits for it to complete. Then it subscribes to the second observable, which hasn’t been doing anything up to this point because it’s cold (and had no subscribers)… and the effect is serialization.

If you want to mimic Promises in your indentifyImage implementation, use the shareReplay operator in your pipeline. For example:

function identifyImage(img) {

const pipeline of(img).pipe(

delay(Math.floor(5000 * Math.random())), // simulated delay

map((img) => 'yep this is a cat'),

shareReplay()

);

pipeline.subscribe(); // No argument needed: just kick off processing

return pipeline;

}The shareReplay operator turns your pipeline into a multicast (hot) pipeline, and also replays past events for subscribers who hop on board after data has already arrived.

We managed to get API call parallelization, while still preserving data order, but we’re calling the API way too much. We need to design a way for the pipeline to only process the data it knows it could use, and terminate early once the four desired cat images are identified.

By definition, we know that full parallelization of the API calls on the input data is not efficient in most cases. The exception is when there are four or less cat pictures in the entire data set, and the last cat picture is at the very end.

Assuming that cat pictures relatively frequent, and spread evenly throughout the input dataset, a more cost-efficient strategy would be to query the API in batches. For each batch returned, we can add the cat images to our result dataset, and then adjust our batch size based on how many slots remain for us to fill.

RxJS provides a bufferCount operator which looks promising, but the buffer size is fixed when the operator is defined. A fancier operator, buffer, uses a second Observable to determine when to cut/emit batches of data. It’s flexible, but also makes our solution dependent on the timing of our source data observable: an extraneous, unimportant factor.

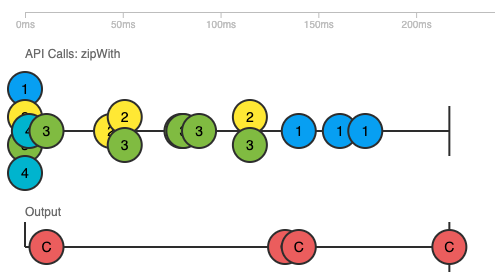

We’d prefer to suspend our input stream entirely, until we’ve processed a batch of results. The zipWith operator comes in handy here! It’ll emit pairs of values from two Observable streams, only when both of them have a value available.

For example:

const batcher$ = new Subject();

sourceImages$.pipe(

zipWith(batcher$), // emits tuples of [image, batcherOutput]

map(([img]) => identifyImage(img)), // we only care about the image

concatAll(),

filter(isCatImage),

take(4)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);The batcher$ stream controls when each source image goes through the pipeline. If we call batcher$.next() four times in succession, four images will immediately go into processing (assuming four images are available to process).

How do we initialize and manage batcher$?

We know that, when an image comes through that isn’t a cat, we want to call batcher$.next() to add another image into processing. If an image is a cat, we don’t need to trigger the batcher, because that output “slot” is filled.

So we now have actions we want to take for both the positives and negatives of our filter operator… meaning that we need something more robust than filter. Enter the partition utility, which splits an Observable stream into two streams for the positive and negative items against a filter!

Since we are creating (and eventually subscribing to) two streams with the same source pipeline, we need to “share()” the pipeline to ensure that we aren’t double-calling the API. See the hot versus cold section for details.

const batcher$ = new Subject();

const [cats$, notCats$] = partition(

sourceImages$.pipe(

zipWith(batcher$),

map(([img]) => identifyImage(img)),

concatAll(),

share() // To prevent double-processing

),

isCatImage

);With the cats$ stream, we do the same thing we’ve been doing:

cats$.pipe(

take(4)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);With notCats$, we need to queue another image for processing on each negative value:

// No need to pass a value to next().

// batcher$ is just a sentinel.

notCats$.subscribe(() => batcher$.next());Nothing will run unless batcher$ is primed with a few next() calls. The initial number of calls will determine the level of parallelism. Since we need four cat images, we’ll set the parallelism to four as well:

// Or, just use a for-loop!

range(1, 4).subscribe(() => batcher$.next());The initial run will send off four API calls at once. The pipeline will maintain four in-flight API calls until one of them returns with a cat. Each cat received will effectively decrement the parallelism, preventing us from over-querying the API after we’ve already received our four cats.

Here’s the final pipeline we created:

const NUM_CATS = 4;

const batcher$ = new Subject();

const [cats$, notCats$] = partition(

sourceImages$.pipe(

zipWith(batcher$),

map(([img]) => identifyImage(img)),

concatAll(),

share()

),

isCatImage

);

cats$.pipe(

take(NUM_CATS)

).subscribe(sendToMyPhone);

notCats$.subscribe(() => batcher$.next());

range(1, NUM_CATS).subscribe(() => batcher$.next());Although it got a little unweildy, this architecture does everything we wanted it to: identified and filtered a specific number of cat images out of a large input set, using parallel processing while also being frugal about extraneous API calls.

This simple problem statement and exercise highlights many key concepts in RxJS:

- Observable streams aren’t limited to containing data. They are also useful in scheduling and behavioral control of pipelines.

- Cold observables are lazy, a behavior that often leads to counterintuitive results when multiple subscribers are involved. If you only want a pipeline run once,

share()it. - Pipelines don’t have “memory” on their own. Changing future behavior based on past results requires creative solutions.

RxJS can be incredibly difficult to wrap one’s head around, and complicated to write.

If your team is slowed down or blocked by an exotic pipeline you wrote, I encourage you to remember: for-loops are perfectly acceptable.

Don’t sacrifice readability for glamor and elegance.

But when the opportunity to wrestle with RxJS does arise, I find that the satisfaction of a solid solution is worth the puzzling challenge!

My hope is that this little exploration satisfied your curiosity too.